The young boy looked up in wonder, at the morning sun, rising above the trees. There was a line of them, along the slow river which flowed, far away. As it rose, it made the flowing river, to turn into a shining silver\gold combination. He closed his eyes and still the shadow of the bright light, remained in his brain, as if the sharp reflection of the sun, still remained. The flash reminded him, of that light he had seen, before the explosion, which changed his life.

He shivered as he lay on the ground, half up, leaning on his elbow, watching the day dawn, and turn to morn. He moaned slowly, as the ghost pain from his missing left legs, rose again. He tried not to start crying, so early in the day, as he did not want the village children, to call him a crybaby again. He closed his eyes again, trying to take long breaths, in and out, as his father had taught him, to calm his mind and body. When he opened them again later, he saw that the reflection of the sun, had gotten weaker, and the river appeared darker, against the green and brown of the trees.

He realized he was thirsty and started to crawl on the ground, towards the hand pump, in the shade of a nearby tree. It was where the street to the temple ended, from the heart of the Brahmin section of the village. He found a container with some left over water, and raised it, and took a long draught right down his open face, and down his parched gullet. Some spilled, but he did not mind as the cool water felt good, and his thirst was gone. He turned and looked down the Temple Street, and watched a stray dog walking away. He did not like dogs and was glad it wasn’t coming, for water.

He had never been inside the temple, or even the Brahmin section of the village. His sister had gone there to steal cow droppings, from their cows, when they went to graze, for his mother’s open fire. She mixed it with straw and made cow dung patties sun dried on their outside wall. His mother used the dried fuel and twigs as fuel. His eyes would often glaze, lying in that smoke, and soot filled hut. His mother cooked the family meal of cheap rice, and whatever they could afford, that day.

Mother had changed a lot, since the wicked men came, and took his father away. He had already suffered his injuries and was lying in his home, on the thick cotton sheet, in his corner quietly. He had heard his father talking and the man yelling at him, outside. Then other voices joined in, harsher and sharper. His father was saying “I have a lame child at home from this unholy war, please there is no one, to take care of my three children and my wife.”

“Take him away,” Came the voice of a man, who seemed high, as if on a horse.

“No, unhand me, No,” I heard my father cry out, as others dragged him away, kicking and shouting.

It had been three years since then and his mother had no time to play with him now. They had been so happy, as she would play with him in the mornings, after all her chores were done. He would laugh at her stories and all his pain would be forgotten. She was magical, she turned his long troubled nights, into a wonderful day. She whispered softly to him “My happiest baby,” and crushed him to her chest. They would cuddle together and play, without a care in the world. They laughed a lot together, happy in their togetherness

Now she would feed the family in the mornings and his older siblings would go off to the village school, as she went off to work. She is a maid in one of the merchant family’s, big brick home. It was a big whitewashed wonder, with lots of people. She worked all day cleaning and washing and anything else that needed doing, for such a large family. She returned in the evenings and made the evening meal, and fed and put them to bed, and slept herself.

“Our school is also a brick building, each class has big windows, with glass!” his sister had told him with awe, when she returned, from her first day.

The boy wondered what it would be, to be, in a room, with big windows. He could not imagine a place, where you could look out, at any time. She told him her class room was bigger than 4 of their huts, and had high walls, and a peaked clay tile orange roof. He wondered what it would be like to be in a strong building in the monsoons, would the rain still sound as loud?

He knew he would never go to school, and he was happy, for his sister. She pressed and massaged his left over thighs, where his legs had been cut off, after the blinding explosion. He liked it when she did that, and he smiled, for the first time that day. Then she heard her mother calling her, and she rushed off, leaving him on his sheet, in his corner, of his home.

“Come here sweat girl,” he heard a man’s voice, who sounded like the merchant, for whom his mother worked.

“She is very young and shy,” my mother said.

“Well, once she starts working, she will be fine,” the man said. “What good is it to you, to educate this girl, as I can help you, if you need more money? Let her come for work also, and I will increase your salary. You are lucky, your middle boy can continue to go to school.”

“She is too young,” my mother said, “She has to take care of my lame son, when she comes from school.” The man would not listen and soon left.

The boy became lonelier. He now had to fend for himself, all day. He would eat what his mother left him, and on days when the weather was nice, and he had the energy, he would crawl out. He was wary of dogs, as he had been almost bitten once, His brother had come and chased two curs away, just in time, as they snarled and snapped at him, in the street. Now he had no one, and so ventured out less often. Today he left the well and slowly crawled back home as the afternoon approached, and he wanted to be back, in his shady hut.

One night he heard his sister crying, “I do not want to go there, any more, mother.” She cried between sobs and he could see her shoulders shaking, as she heaved and wailed. Her mother reached out her arms and wrapped her and pulled her to her bosom. She held her in her arms and shushed her, trying to stop her crying. “They hurt me,” she murmured and mother continued to hold her, and tried to comfort her.

His sister stopped massaging his thighs, and she seemed to be afraid to touch his flesh. He would reach out to her as before, and she would retreat, as if afraid. This frightened the little boy even more, as he thought he had turned into some monster. He knew that he was scaring his dear sister, just as he had hurt his mom, with the blast. He hurt more, every day, now, and the pain, would not go. Even when he breathed, like his father had taught him, the pain stayed there, and arose and fell in pulses of heat.

He was losing his memory of his father, he realized one day. He could not hear his voice in his ear, telling him that he will take him to the city hospital, and that he would get better soon. He missed his strong arms around him, making him so warm and close and secure in his world. He learnt how to bear his pain, and not cry. He knew his father was taken away, because of him, as he had heard him pleading with them and they must have taken his father, because he was a bad son. Even if he cried, it did not matter, as there was no one there. So he just lay on his cotton sheet, in his corner of his world, alone, and unwanted.

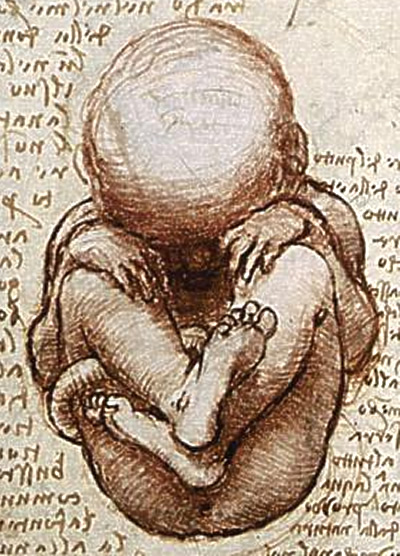

The long nights became especially painful for him, as he tried to be quite, so his mother could sleep. The nights when he heard his sister crying silently, were the worst, for him. They were so close, and yet so far, and he felt like screaming. Then he would remember his sleeping mother, and his father’s gift. He would cuddle himself, into a ball of pain, and breathe. He would take one long incoming breath. Then a slow outgoing breath. He would continue his breathing moment by moment, aware of his pain; and dying a little bit more, with each breath.He eagerly awaited the dawn to escape a little, whenever he had the strength..

His life force slipped away in the winter night, quietly, without a murmur. Next morning his mother picked him up, and took him out, and laid him in the sun, to clean him. She washed him and looked lovingly at his beautiful face, and prepared for his last rites. The people from the neighboring huts came, and helped prepare him, for his final journey. All she could remember was his smiling and giggling face as a baby.

As the men lifted and took him away, a single tear fell from his mother’s eyes. “My happiest baby,,,,,” repeated again, and again, was all they heard, as they took him away.

No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. -Robert Frost, poet (26 Mar 1874-1963)